Mercifully, no blows were forthcoming. They agreed to perform the play as written

and to speak of changes—“emendations,” William called them—the next day. Soon after the men parted, Linda appeared, offering William a knowing and sympathetic look.

“William,” she said, “it will not do you much good to complain. Patrick will not listen. You must show him.”

“Yes, I suppose I must,” he replied with a rueful look. “I will work on it.” William turned and saw that I remained within hearing. My manner must have telegraphed my alarm, as he held out his hand to me. I moved toward him cautiously and took it.

“Mel,” he began, bending on one knee before me, gently taking my hand in his, “at tonight’s performance, you must play Topsy as you have studied it. I will work on changes with Patrick tomorrow. Do you understand?” I nodded.

“You will not fight with Patrick?” I asked. William put his hands on my shoulders and held them firmly.

“No, my boy,” he replied. “Patrick is our friend. We may argue, but we will never engage in fisticuffs. You have my word on that.”

“You will see, Mel,” he whispered in my ear, “We no longer have to be portrayed in such servile ways. The additions I will be making will show the true strength of our enslaved people!” William released me and stood.

“Linda,” he said, his voice resuming its usual jollity, “I will need your aid in reproducing the courageous speech from the Aiken production that Patrick most willfully omitted. We will also commit ourselves to providing Topsy with more to do than behave as a simple-minded imp! The audience shall see a fine play tomorrow!”

“They certainly shall,” Linda smiled, cheered by William’s now sanguine mood. “I must go begin supper before I can assist you. I have prepared your favorite, lamb stew.”

“Delightful, my darling!” William replied. “I will work on the emendations so that they will be ready for tomorrow!”

William disappeared into the carriage in which I had slept earlier, while Linda occupied herself in the preparation of the evening meal.

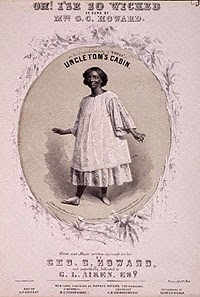

I continued to practice my tumbling and the words I was told to commit to memory. I was to repeat “I ‘spects I’s de wickedest critter in de world” several times, and to sing* the following lines:

Oh! white-folks I was never born,

Aunt Sue raise me on de corn,

Sends me errands night and morn,

Ching a ring a ring a ricked.

Sends me errands night and morn,

Ching a ring a ring a ricked.

She

used to knock me on de floor,

Den bang my head agin de door,

And tare my hair out by de core,

Oh! cause I was so wicked.

Black

folk can't do naught they say,

I guess I'll teach some how to play,

And dance about dis time ob day,

Ching a ring a bang goes de breakdown.

Oh! Massa Clare, he bring me here,

Put me in Miss Feely's care,

Don't I make dat lady stare,

Ching a ring, a ring a ricked.

She has me taken cloth'd and fed,

Den sends me up to make her bed,

When I

puts de foot into de head,

Oh! I'se so awful wicked.

Oh! I'se so awful wicked.

I'se

dark Topsy, as you see,

None of your half and half for me,

Black or white it's best to be,

Ching a ring a hop, goes de breakdown.

None of your half and half for me,

Black or white it's best to be,

Ching a ring a hop, goes de breakdown.

Oh! dere is one, will come and say,

Be good, Topsy, learn to pray,

And raise her buful hands dat way,

Ching a ring a ring a ricked.

And raise her buful hands dat way,

Ching a ring a ring a ricked.

'Tis LITTLE EVA, kind and fair,

Says if I's good I will go dere,

But den I tells her, I don't care,

Oh! ain't I very wicked?

Eat de cake and hoe de corn,

I'se de gal dat ne'er was born,

But 'spects I grow'd up one dark morn

Ching a ring a smash goes de breakdown.

No comments:

Post a Comment